Plenty of writers resist this idea. They feel that revising a story according to the likes and dislikes of an audience is somehow akin to prostitution. If you really feel that way, I won’t try to change your mind. You’ll save on charges at Copy Cop, too, because you won’t have to show anyone your story in the first place. In fact (he said snottily), if you really feel that way, why bother to publish at all?—Stephen King

Before life around the world started to imitate art, in particular a Stephen King novel, I found myself engaged in a few ways with responding to writing. It’s the best way—maybe the only way—for authors to tell whether they’re getting their messages across to readers. It can also yield suggestions for delivering those messages more powerfully and clearly. Middle and high school classes where I substitute were doing it and I was, too, as a contest judge.

On a nearly annual basis, Denver Woman’s Press Club runs a contest for aspiring authors to submit samples of their work for a chance to capture a small cash prize. Also in exchange for their efforts and their entry fees, they have an assurance that at least two professional writers or editors will respond to their work. Our feedback is akin to a mini manuscript evaluation, even though that would be more comprehensive.

The Good, The Bad And Suggestions

Since judges come from various backgrounds, we begin our participation by attending a session to share some pointers on providing constructive feedback.

One of the most important pointers, from the perspective of one who is sometimes overly blunt, is to remember that we’re judging stories and how well they’re told, not authors or their experiences, choices, or lives. Those who enter the Unknown Writers’ Contest often choose topics that relate to traumatic episodes in their lives involving things like child abuse, illness, dementia, and hospitalization. Regardless of the quality of the writing, we need to acknowledge the courage involved in writing about such matters.

We are reminded that we are not critics, but responders, nor are we to do the work of proofreaders or editors. I’m glad to hear that because when I taught freshman composition at Metropolitan State University of Denver (then Metropolitan State College), I know I spent more time on some papers than the authors did. I felt responsible not just to make suggestions for revisions, but also to demonstrate how to make those revisions.

That brings up another point: We frame our feedback as suggestions and as one reader’s reaction, not anything more authoritarian.

We always, always, always find something outstanding—even if it’s just that emotion shines through—and provide encouragement.

Vampire Provides A Model

The contest comprises three genres—nonfiction, fiction, and poetry—and feedback varies accordingly. Logical flow is more important in nonfiction, while character and plot are central to fiction.

But, regardless of genre, the consensus at the clubhouse is that writers can absorb three main pieces of feedback. So we follow a formula that gives a general response to the piece, approximately three areas that could use work, and an ending paragraph. An anonymous example has floated around the club for a few years and it goes like this:

I enjoyed the idea of a slacker vampire, a millennial dude with low motivation who sees no point in moving fast, acquiring wealth and power, or making a long-term commitment that might force him to spend eternity with some boring female vampire. This guy just wants to do whatever comes easy, whether that’s drinking human blood instead of animal blood or simply sleeping the day away and watching the tube. There was plenty of humor in this break from traditional vampire stereotypes: I found it funny that he liked eating the rich and stupid, not because it fits the vampire milieu but because they’re so annoying!

If the writer would like to further develop this piece, here are some thoughts to consider:

- I didn’t have a clear sense of what was at stake for Bryan (no pun intended). I felt that the story needed a conflict. No doubt his victims might prefer not to be eaten, but it’s Bryan who is the focus of the story. I wanted to know what Bryan has to gain or lose, what obstacle he needs to overcome, what conflict he needs to resolve either within himself or with others.

- It struck me that Bryan’s ennui is at the heart of his character development. If so, then I would like to see his ennui somehow drive the plot. What is it about being a slacker that could create a problem for a vampire?

- I suggest doing more copyediting. …

This story shows potential: the main character is well drawn, the sensory description rich, and the slacker premise engaging. Thanks for a fun read.

Like the press club, the middle schoolers were guided by advice about how to start their responses. These included phrases such as I can tell, I gather, I think you’re trying to prove, I’m curious, I wonder, you might try, and have you thought about. Students were instructed to be specific, ask questions, and offer advice.

The Right Stage For Feedback

While school students need to work within their teachers’ frameworks, Stephen King explains his process for obtaining feedback in On Writing: A Memoir of Writing. He emphasizes that writers should share their work at the appropriate stage, when it is in nearly final draft, and they should share it only with people whose opinions they respect.

His “Ideal Reader” is his wife, Tabitha, and, after she looks at his manuscripts, he generally sends them to several others for their responses.

“When you give out six or eight copies of a book, you get back six or eight highly subjective opinions about what’s good and what’s bad in it.” When opinions are unanimous, he revises accordingly. When opinions are evenly divided, “a tie goes to the writer,” he states.

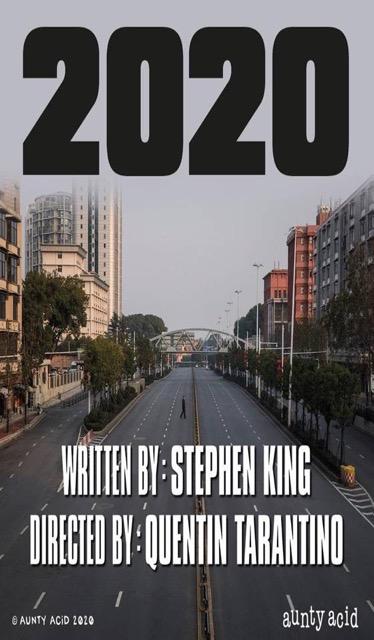

King’s 1978 dystopian novel The Stand tells of a viral pandemic that wiped most of humanity off of the planet. He says he understands when people make comparisons between the book and current events, and offers a simple apology. “I’m sorry,” he says in an NPR article (https://www.npr.org/2020/04/08/829298135/stephen-king-is-sorry-you-feel-like-youre-stuck-in-a-stephen-king-novel).

Meanwhile, he reports he’s dealing with cabin fever by making “wonderful progress on a novel because there’s really not too much to do and it’s a good way to get away from the fear.”

My guest editor for this post was Vicky Tangi, who teaches English as a Second Language to adults and whose writing has been appeared in Louisiana Literature, the Journal of College Writing, The Advocate and numerous literary anthologies.

If you have a manuscript and you’d like my response to it or a more comprehensive evaluation, please let me know.